The small house known as Brandywine Mansion is the oldest structure in the Lukens

Historic District. The original section, dating to the mid-1700s was built by the

Flemings, early landowners in what is now Coatesville.

In March 1787, the property was sold to Moses Coates, who added the mansion's

larger west section about 1788. It is believed President George Washington stopped

at Brandywine Mansion in 1794 in route to Philadelphia after quelling the Whiskey

Rebellion in western Pennsylvania.

Coates sold the house and 110.5 acres to Jesse Kersey and ironmaster Isaac Pennock

in July 1810. While Kersey divided lots along the turnpike - a development called

Coates Villa - Pennock converted the farm's sawmill to a rolling mill. His business,

Brandywine Iron Works & Nail Factory, was the genesis of Lukens, Inc.

Pennock's son-in-law and partner, Dr. Charles Lukens, moved to Brandywine Mansion

in 1816, when he assumed management of the mill. America's first boiler plates were

rolled under Dr. Lukens direction in 1818. His death in 1825 forced his widow, Rebecca

Webb Pennock Lukens, to run the mill herself. Known for possessing remarkable business

acumen, Mrs. Lukens lived in the house until her death in 1854.

Much later, Brandywine Mansion became part of Lukens' company store and a large

building was erected against it. This addition which did not contribute to the building's

era of primary historical significance was removed in the fall of 2009. The long range

goal of restoration of the house has begun.

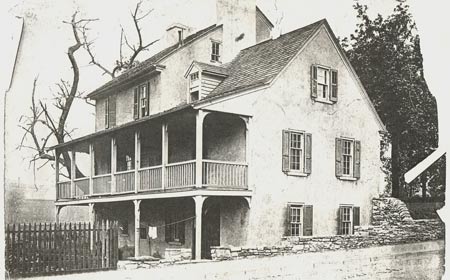

Brandywine Manshion is located on South First Avenue, and is nearly flush with

the current thoroughfare. Its core construction consists of two sections: a 2-1/2-story,

stucco-over-stone (east) section, two bays wide, built circa 1739, is attributed to

William or Peter Fleming; and a 2-1/2-story (plus basement), stucco-over-stone (west)

addition, three bays wide ad slightly deeper, built 1788 by Moses Coates. Fronting

these two early sections on the south is a two-level, shed-roofed porch (now enclosed).

These elements comprise the house in which Rebecca Lukens lived.

Although several substantial additions were added to the house, primarily in

the early 20th century when the house became the Lukens Employee Cooperative Store,

the essential elements of Rebecca Lukens' house survived, including: the original

massing, thick stone walls, roof lines, two out of three chimneys, most of the window

and door openings, the floor plans (one room on each floor in the earliest section,

a three-room plan on each floor of the 1788 section), interior bearing walls, chimney

foundations, fireplaces (now sealed), dormers, the porch (albeit altered), curved

bullnose corners on the window openings, and floor and attic framing. Many early 6-over-9

window sash survive as well.

In style and type, the two early core sections follow vernacular forms that were

well established in the Mid-Atlantic region by the 18th century. The earliest east

section, with its single room (pen) on each floor and a gable-end chimney (now gone)

was typical of first-generation farmhouses following British vernacular traditions.

The later 1788 section is a combination of farmhouse prototypes favored by German

immigrants, with its three-room plan (one room deep on one side, two rooms deep on

the other), and the British preference for gable-end chimneys (unlike the Germans,

who favored interior, or center chimneys). At Brandywine, a large cooking fireplace

with a wide rectangular opening (now closed) stands on the outer east wall of the

"hall" which abuts the first section, while two smaller heating fireplaces

(also sealed) stand back-to-back and diagonally across the corner formed by the outer

west gable-end wall and the interior masonry bearing wall dividing the two smaller

rooms. These corner fireplaces are connected to a common chimney. The same room and

fireplace arrangement is mimicked on the second floor.

In addition, the core sections of the house display 18th-century building traditions

common in the Delaware Valley, namely stucco over stone construction, curved bullnose

corners on the perimeter window and door openings, and simply molded, shadow boxed

eaves. Furthermore, according to local practice, the house is built into an embankment

so that the basement is exposed on the down-slope (south) elevation which is fronted

by a two-level porch. This porch may have been enclosed with beaded boards in the

early 20th century when the house was converted to the Lukens Employee Cooperative

Store.

Not surprisingly, given their vernacular origins, the original fenestration of

the two early sections is irregular and asymmetrical. While approximately one-third

of the existing door and window openings are alterations (mostly dating from the years

when the structure was a company store), good surviving physical evidence and early

photographs attest to the location and size of the original fenestration. The earliest

surviving sash, which is 6-over-9 double-hung, survives at numerous windows. Two gabled,

frame dormers with 6-over-6 sash also survive in the first section. (Another dormer

was removed to accommodate the "hyphen" which connects the second floors

of the original house and the store addition). Two sets of original exterior solid

board shutters with wrought-iron strap hinges flank windows on the south.

In addition to the room configurations, plaster walls and ceiling, and

sealed fireplaces, other early extant interior features include simply molded window

and door frames; a four-light transom over the south, center door; some surviving

raised-panel interior doors; a board-enclosed attic stair; and, most notably, a raised-panel

wooden breastpiece over the rectangular fireplace opening that stands in the first

floor of the early section.

Floors are narrow oak strips throughout, a later alteration. The main stairway

probably dates from the mid-1800s, and features a heavy, turned newel post incised

with simple designs and topped by a ball finial.

The attics have beaded-board or plaster partition walls, and the basement retains

three chimney foundations with arched or rectangular openings.

The following is from "Reminiscences" by Clara Huston Miller.

It is Isabella Lukens Huston, Rebecca Lukens, elder daughter, as she describes the

home at Brandywine.

"My father and mother removed to this place, near the village of Coatesville,

a very few years after their marriage, and found it much out of repair. My father

became engaged in the iron business, and my mother exerted herself in improving the

surroundings of the mansion. This consisted of two houses connected, but built at

different times. The older and lower house, thought then to be very ancient, must

now date back one hundred and twenty-five years, although we have no record but tradition.

The higher part was of comparatively recent date, when my mother first occupied it,

so that it is now nearly eighty years since its erection by Moses Coates.

"My mother found everything very dilapidated, both in the house and around

it, and the first thing she effected was to plant several weeping-willow trees, which

were at that time much admired. She held the trees while the earth was filled in,

and they afterwards became the peculiar feature of the Old Home.

"My father died in a few years having scarcely made a fair start in business.

My mother then carried on the rolling-mill at his request, and developed in herself

remarkable strength of mind and business ability. For some years she did not feel

in circumstances to improve the house, although the property had now become hers,

by the will of her father; but as the severe pressure gradually relaxed, she added,

from time to time, such alterations as her judgment and tastes dictated. She enlarged

and cultivated her grounds. She built a long piazza to the south of the house, with

wide steps descending to the ground, and a portico at the front entrance.

"Being very fond of flowers and shrubbery, her home became a blooming bower.

I have stood on the south piazza, with roses and honeysuckle beneath and around me,

and gazed with rapture upon the beautiful wooded scene before me, first the garden,

with its various greens of ornamental shrubbery, then beyond that the old apple orchard,

and rising above all the forest-crowned hills in the distance. To the right rose the

cheerful chimney of the rolling-mill; to the left, a sweep of our beautiful Great

Valley, with fair meadows and fields lying in the sun and a meandering stream, making

the view perfect. Descending the piazza steps we were ushered by a half-circular walk

into the flower garden; then by a straight path bordered with blossoms to the summer-house.

This was an octagon, covered with the clinging branches of a great prairie rose. Beyond

this was a lovely greensward, with a pond filled with gold fish, and shaded by an

English hawthorn and some shapely apple trees.

"The enclosure to the front of the house was narrower and more shaded. But my mother added a piece of ground farther out, which she called her 'sunny spot,' and enriched it, planting it with the loveliest roses. By the old willow trees, she grew ivies, so that they were truly all in all 'The last green tree in autumn, 'The first green tree in spring.'

"The interior of the house was comfortable, so far as I recollect it, for

with its earlier history my mind was not familiar, but the rooms were irregular, and

the ceilings unavoidable low, although my mother made every alteration she could think

of, to add to the comfort and convenience of her home, and was very fond of hickory

wood fires burning in the open Franklin stoves, for which there were several. Although

after I grew up, coal fires began to supersede those of wood, yet my mother, a great

sufferer at all time from asthma, regarded coal as adding to her painful disease,

so that we burned wood much of the time. Often on a cold winter morning, I could scarcely

get warm before noon but in the evenings it was lovely. We often prolonged the twilight

hour, gathered around the glowing fire, my sisters and myself sometimes seated on

the floor, seeing many fanciful pictures in the changing embers, and following our

dear mother with her beautiful gift of language and vivid imagination, back into the

past, or forward into the uncertain future. Of all the recollections of early life

stereotyped upon memory, this is the most forcible and the dearest.

"In altering her house, my mother did not hesitate to pull down a stairway

here, and project another there, as best suited her, but the long piazza added more

than any other improvement to the comfort of the family mansion. Situated upon the

side of a hall, according to the ancient prevailing idea of a shelter from the wind

and convenience to springs of water, we entered the house upon level ground, and walking

across the sitting-room, found ourselves looking out of second-story windows, with

the kitchen and the dining-room in the basement. Thus the piazza enlarged the house.

My mother's favourite resort in summer evenings was at the east end, overlooking the

road, where she held many conversations with the passers-by, and had a word and smile

for all. Above her, and around her, hung the cages of sister Annie's singing birds.

"The long piazza was used as a dining-room for the wedding tables of my

sister Martha and myself. It was enclosed with canvas for privacy, and to exclude

in measure the chilly airs of autumn and spring, the respective seasons of our weddings.

This was festooned with wreaths of evergreen. The uprights which supported the arches

over the table, and some of the candle-brackets, still remain. These dumb memorials

are very touching, when we think of the head and the heart that designed them, long

since passed away.

"An oak table is now in the cellar which formerly stood in the kitchen,

from which, in Revolutionary times, General Washington and his staff dined."

The following is from "Reminiscences", by Clara Huston Miller, Isabella Lukens Huston's daughter and Rebecca Lukens' granddaughter. It is her recollections of Brandywine Mansion.

I can remember Brandywine Mansion, Grandmother's home, before it was much changed.

There was an open space between our lawn and hers, on which stood, well back from

the road, her barn and stables.

Her house did not front the road, but faced ours and was very irregular in construction,

having been much added to and altered during the many years since it had been built

by Moses Coates (for whom the town was named) and especially during her long residence

there. It was built on the side of a hill, which made the front hall, at one end,

and the sitting-room door, at the other, open almost on a level with the upper garden,

which was planted with roses, old-fashioned flower border and shrubs; weeping-willow

trees shaded the house, while trumpet-flower vines climbed to the roof and yellow

cocorus bushes grew at its base. The newer end was higher than the old part and a

porticoed door led into the front hall, from which a stair led to the dining-room

below and another to the bed-chambers above. Into this hall opened a small library

and the large parlor, and from it a corridor ran to the older, original building,

where the sitting-room, on its far side, had a door leading out on the long, wide

porch, of which I have already spoken, and which extended the full length of the house.

Grandmother's bedroom was the connecting link between sitting-room and parlor, but

opened only into the corridor; there was a paneled closet in it where cakes and goodies

were kept. Underneath the port, and darkened by it, although also opening into the

garden, were the dining-room, cellars (stone-flagged) and large kitchen, with open

hearth, many feet wide, for burning wood in the old days with crane for hanging pots

overhead. From the sitting-room a winding stair led down to the kitchen (which opened

directly into the dining-room); another flight led to the second storey.

The lower garden contained a bath-house with tub installed, where was obtainable,

at any time, a dip into cold, running, spring-water. Many years after, I saw and used

similar ones when visiting the prehistoric, ruined cities of Yucatan, an, curious

coincidence, I had with me there a descendent of Grandmother Lukens — Elizabeth

Gibbons, one generation further removed than myself. Vegetables and flowers grew in

friendly proximity in this lower garden. I dimly remember that a grape-arbor (we would

call it a pergola today) ran down its middle towards a babbling brook which formed

its southern boundary, but before the stream was reached a pond had been shaped and

stocked with gold-fish – with a summerhouse on its nearer side; weeping-willows

overhung it, and thus a Chinese landscape greeted the eyes. Whether this was intentional

or not I do not know but believe that it may well have been so. There was much intercourse

then between the United States and China, and a great deal of commerce existed through

the carrying capacity of our many sailing-ships. The weeping-willow was then a comparatively

new tree, imported from "far Cathay" and, as Americans ate off their "willow

pattern" plates, they knew, from infancy, what a Chinese garden looked like.